Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is an uncompromising, rigorous and disciplined work of modernist cinema—a twisty, difficult film which undermines all expectations, keeping the spectator at a critical distance throughout yet continually holding our attention via mesmerizing visuals and knotty moral and ethical conundrums. Gorgeously shot and edited, The Master looks magnificent on the big screen, and the relationship between the film’s two central characters generates a lot of heat – the work on display is about as explosive and compelling as screen acting gets.

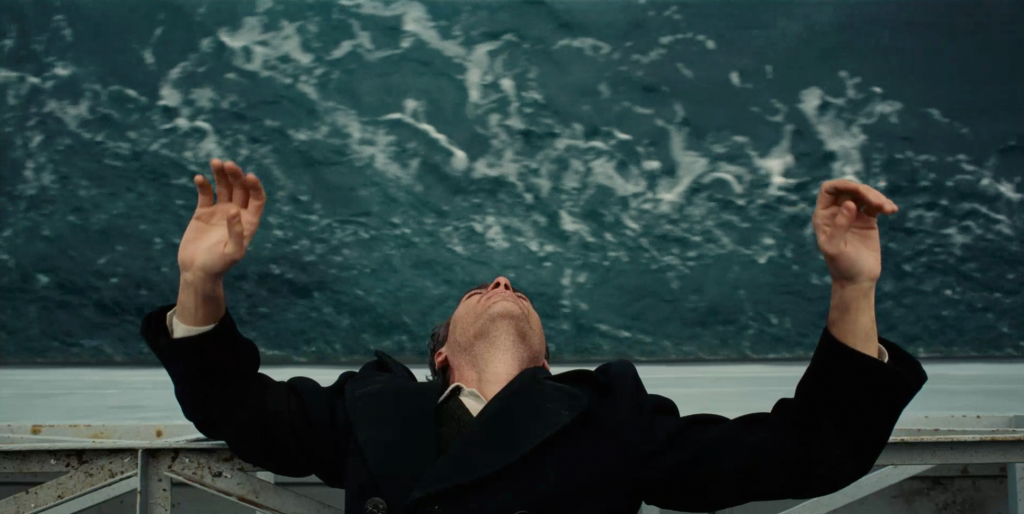

Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix play deeply flawed, self-destructive men in mid-century America – one a charismatic megalomaniac with untapped resources of anger and the other a feral and self-loathing World War II veteran drifting through life fueled by toxic combinations of liquid refreshment which would kill the average, or should I say normal, joe. The relationship between Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd and Phoenix’ Freddie Quell is, well, very strange. Dodd’s Apollonian instincts both feed on and wish to tame Freddie’s chaotic impulses. Their’s is a love story of sorts (and the soundtrack of period pop songs works to underscore the attraction). Is it sexual, paternal, fueled by competitive instincts or jealousy? Is Freddie looking for a place to belong? Does he jump on Dodd’s ship simply to return to the comforting rhythms of life on the open sea? Is Dodd resisting his own self-imposed narrative (a brand of American hucksterism as old as P.T. Barnum)? The film doesn’t really invest in answering any of these questions. The final forty-five minutes or so are more explicitly discursive, playing with space and time as Picasso once played with shape, line and volume. There are no moments of discovery, no climatic revelations, no bowling pins or milkshakes to drink. We are pretty much left on our own to tease out an interpretative set of responses. Finally, as everyone by now knows, Dodd leads a group of passionate followers in highly questionable cultic activities (one part hypnosis, one part chimeric expressionism, one part psychotherapy). Quell is his most fascinating subject. Scientologists should probably be concerned as this is some weird ass shit. Though she does far more than hover at the margins of the narrative, I don’t know exactly where to place Amy Adams’ work in this brief collection of first responses, but she is great, one of Anderson’s strongest female characters ever. I’ll have to just keep sorting through my impressions. Like every other review I’ve read, the film certainly demands a second viewing (many will regret their first and fair enough). Given the paucity of decent films in 2012 (all told about three truly deserving titles over the last nine months and two of those foreign films released in 2011), it shouldn’t take too much impetus to haul my ass back into the cinema.

I haven’t had time to process my viewing yet, but I know enough to say that it is indeed a mesmerizing, enormously powerful film. The acting from Hoffman, Phoenix and Adams is consistently great (and I agree with Jeff that Anderson gives Amy Adams a lot to do in the film). I haven’t read any background on the film, so I don’t know what Phoenix did to prepare but he makes himself so hunched and gaunt that just his shape externalizes the twisted character within. So much of the film is close-ups of the faces of the three main characters while they speak (or in Phoenix’s case, listen); somehow Hoffman, in particular, manages to minutely change his facial structure between moments of intensity during processing sessions and moments of bonhomie in the film. The Johnny Greenwood score is less intrusive than in There Will be Blood (though I liked it there too).

Two questions: what is meant to have happened in the relationship between Dodd and Quell between the First Phoenix Congress and the meeting again in England? And, I stayed a few minutes of the credits before leaving, but I noticed that the film seemed to have lasted only about 2 hours and 10 minutes, not the 2 hours and 30 minutes listed as the running time. Are the credits really that long? Is the movie shorter than advertised? Or is there some crucial after-credits scene that I missed!

I read it was 137 minutes so, maybe, seven more minutes of credits? That sounds like a lot. As far as the last forty minutes or so . . . I do think the narrative is intentionally elliptical, fragmented. The disorienting temporal cuts between the motorcycle sequence and the Doris Day mother sequence and the England sequence . . . well, I just don’t know. There was a mood, there was a tone, there was the feeling that maybe Freddie could no longer be the man Dodd needed him to be (or maybe it was about Freddie picking a point in the distance and just hurling himself in that direction). Might that have something to do with post-war American masculinity (the last sixty-five years or so)? Some will cry foul that Anderson purposefully does not provide any kind of closure, and there were interesting visual echoes of scenes from TWBB in final fifteen minutes or so of The Master. I do want to see it again. A theatre here in the Cities will be showing it in 70mm (only screen in the metro area that can do so). Might be worth the effort if I can carve out the time.

I’m going to try and see this in 70mm. Our theaters, like most throughout the country, are now only digital. Boston seems to be the closest venue, at the Coolidge Corner Theatre. They’ll have an exclusive 70mm engagement for at least 3 weeks.

Saw this yesterday in Silver Spring, at the AFI Silver theater. The 70mm experience was what I had hoped for. The image was clear, crisp, and at times seemed to glow with a vibrance and warmth I haven’t seen on the screen for some time. I’m thinking especially of a shot late in the film, when Dodd takes Freddy, his daughter, and son-in-law to the desert for one of his “games.” It happens at the end of the scene in which Freddy is instructed to pick a point in the distance and ride a motorcycle as fast as possible to it. He disappears into the distance (we later learn that the point he chose was his old sweetheart Doris’s house). After Dodd realizes Freddy is gone–I mean, real gone–he leads his daughter and son in-law across the sand. Dodd is on foot, and his son-in-law and daughter follow close behind in their car. It’s a very low angle shot, and it is dusk. The image is a dazzling mix of pastel blue and yellow. Anyway, it’s a cool shot.

Anderson did not work with his usual DP but instead went with Mihai Malaimare Jr., who does a beautiful job. As with many Anderson films, there are some fantastic long takes (one of the first of which is a beautiful shot of a young woman modeling a fur coat in a department store).

There’s the typical Anderson here–an interest in the occult, outbursts of violent rage, penetrating one-on-one “interviews” which, slowly but surely, cut deeply into a character’s deepest shame, and strange creativity (Quell’s gift for mixing up some nasty but powerful hootch). More typical, I think, than There Will Be Blood–which I think is a superior film. But that’s saying a lot, because Anderson’s 2007 film is extraordinary. So is The Master, and I would like to see Anderson continue to delve deep into various decades in American history to explore the condition of the American psyche. Boogie Nights gave us the heady, sweaty 70s. There Will Be Blood takes us to the oil boom of the late 19th century, and The Master deals with America just before the Eisenhower era.

I don’t think I can add much to what has already been said about the acting. Both Hoffman and Phoenix are extraordinary. And Johnny Greenwood’s score is great.

I’ll continue to think about this film and I hope to post some more comments.

Did you fly to Maryland? That’s beautiful (no sarcasm).

Yeah, Alicia and I went to D.C. this weekend–a trip we had been wanting to take for some time anyway. With a weekly airfare special, non-stop from Charleston to Reagan National, we couldn’t pass up the opportunity.